menu

Winning in Recovery: Everything You Need to Know about Eating Disorders in Athletes

Winning in Recovery: Everything You Need to Know about Eating Disorders in Athletes

category 4

category 3

category 2

category 1

blog

categories

book your 1:1 call

connect with me

I utilize my own shared recovery experience to provide compassionate recovery care and empower clients to a life of health and wellness.

a Certified Eating Disorder Recovery Coach based in Dallas, Texas.

i'm merrit elizabeth

Looking for information on bulimia specifically?

visit the conquering bulimia blog

I recently had the pleasure of talking with my colleague Registered Dietitian Mary-Lauren Shelton. Mary-Lauren Shelton Vise, RDN, LD, CEDS is a Certified Eating Disorder Registered Dietitian and the founder of Nutrition DiscoveRD® in Dallas, Texas. She is an experienced clinician who has worked with clients in residential, partial hospitalization, intensive outpatient, and inpatient settings. Mary-Lauren provides virtual nutritional counseling throughout several states. She specializes in sports nutrition and treating competitive athletes with eating disorders. In this discussion, Mary-Lauren focuses on eating disorders in athletes and how parents, providers, and coaches can empower those struggling to achieve full recovery.

Would you please start with the basics of the prevalence of eating disorders in athletes and how the culture of competitive women’s sports can lead to eating disorders?

In women’s sports and sports overall, there’s a strong emphasis on performance. Often, it means that the focus is taken away from the athlete’s well-being to focusing on competing and being more competitive in their sport. This may cause them to neglect their body’s needs, resulting in mental, emotional, and physical exhaustion. This commonly leads to developing issues such as low energy availability (LEA), relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S), or an eating disorder.

Initially, athletes often start with harmless intentions in trying new intake patterns or training programs. However, over time, what seemed harmless can escalate into severe problems requiring intervention. Research indicates that many athletes, trainers, and coaches lack adequate knowledge or education about nutrition and proper fueling, leading to detrimental outcomes.

Perfectionism and intense societal pressures to consistently compete and perform create challenges. It becomes especially tough for those who identify strongly as athletes or as an athlete within an individual and specialized sport. High prevalence rates of eating disorders and disordered eating are observed in sports, with one study finding that 13.5% of athletes struggle with an eating disorder and up to 62% of female athletes in weight class and aesthetic sports engage in disordered eating patterns. Another study that was completed this year [2023] for high school athletes found that 52.1% of young female athletes were classified at risk for low energy availability, and 68.6% qualified for eating disorders. So, again, an overwhelmingly large prevalence, especially in our young athletes, which tends to intensify as they get older and further into their sport. Finally, another research article found that 90-95% of college students diagnosed with an eating disorder belong to a fitness facility. That shows that there is a strong correlation between eating disorders and a disordered relationship with movement or sport.

Can you clarify what low energy availability is?

Low energy availability (LEA) is a condition that occurs when an individual or athlete’s energy or fuel intake is insufficient to meet the energy demands required for physical activity and other daily and bodily functions. In other words, it is a state when an athlete is using more energy through exercise or daily activities than they are consuming resulting in low energy availability. This can be viewed as a negative energy balance. If an athlete remains in LEA it can lead to various health issues and negative consequences such as impaired performance, increased risk of injury, decreased bone density, and altered hormones and mood.

Do you see specific sports triggering or normalizing disordered eating behaviors more than others and would you explain why?

We work with a lot of athletes in aesthetic sports, weight-sensitive sports, and endurance sports. We see a ton of gymnasts, dancers, swimmers, wrestlers, soccer players, as well as distance runners and triathletes. Fueling for long-distance and endurance sports requires a substantial amount of fuel which very few athletes can naturally get enough on their own without a fueling plan. Oftentimes, underfueling or inadequate fueling stems from a lack of knowledge in how to properly fuel. Our job is to help our athletes understand their bodies, their bodies’ needs, and how to properly fuel them.

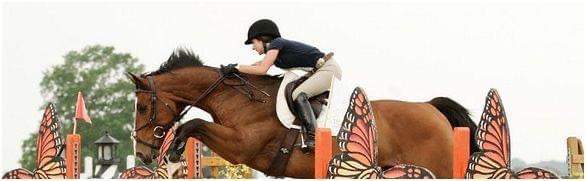

When considering sports and at-risk athletes, certain groups might not immediately come to mind. Equestrians are one group of athletes that people rarely think of as being at risk. Having been a highly competitive equestrian for the majority of my life, I greatly enjoy working with this population. The sport requires substantial physical and energy demands, making fueling challenging, especially when on the road most of the time, and relying on concession stand food or nearby options for the majority of your meals and snacks. Performing Artists also face unique challenges such as being in front of people, being in the spotlight, embodying different characters, and commonly wearing outfits that were not made for them and might not be suited for their bodies. This can be particularly uncomfortable.

Disordered eating is prevalent across various sports and performing arts, where weight cycling is normalized, emphasizing appearance over performance and overall well-being. Dancers, swimmers, wrestlers, and gymnasts, for instance, wear tight or revealing clothing, intensifying the focus on body image. This becomes a challenge, especially for activities like swimming, where individuals may be hesitant to eat a substantial meal before jumping into the pool. Instead of encouraging restrictions, it’s important to help them develop a fuel plan that meets their nutritional needs. Practices like public weighing and measuring, often done in locker rooms or during uniform try-ons, can be incredibly harmful, especially for those struggling with body image or eating disorders.

For our weight class athletes in sports, like wrestling, some of our athletes identify that they would perform better in a different weight class that is aligned more with their normal weight. However, there is only one spot per weight class so if that spot is already filled, this can lead to pressure from the coach for you to find a way to get to that other weight class in order to compete and to fill the spot. Again, prioritizing the team’s needs over the athlete’s well-being and performance.

In my case, perfectionism was the major driving force of my illness. I always thought “I can be better or do better” and I was constantly praised for that attitude. No one understood that their rewarding comments were empowering the eating disorder because no one knew at the time about my illness. Will you please discuss how certain traits that make student-athletes highly successful in sports and in the classroom also lead to eating disorders?

There are so many factors that overlap and what I see, especially with my athletes, is a lot of times what makes an athlete so good at their sport also makes them really good at their eating disorder. That can be really harmful because more often than not, our athletes will hide the fact that they’re struggling. Or they think that it’s just normal because a lot of our athletes believe “I need to be thinner or I need to be lighter to be stronger and faster and more competitive.” Many of those traits carry over to fuel the eating disorder, but it also aligns with the sport, unfortunately making it a challenging cycle. We see a lot of people pleasing in our eating disorder clients and athletes, and the perfectionism piece of that is huge. Athletes are highly competitive, so there may be some competitive thinness between teammates or themselves. They are always willing to do more to be better. It is challenging for athletes to realize that enough can be enough, and we don’t have to keep going and pushing our bodies to the limits or beyond. Another characteristic that makes an athlete so great is that they are so motivated and driven. They are frequently praised for their self-control and dedication and this can fuel the eating disorder as well. Little off-the-wall comments really are difficult for athletes with eating disorders such as, “You’re so controlled around food, you eat so healthy”, “I wish I looked like you”, or “You’re so dedicated, I could never do that”. Also, most of our athletes are pretty Type A. They’re very on top of it. Very organized. “Everything is great”. They are just a model student. There is a lot of people pleasing, and so that can be challenging to kind of separate the two.

Will you please walk me through the signs and symptoms that you typically see in an athlete who is struggling with an eating disorder?

There are many different signs and symptoms- a lot of times we will see a sudden fear of weight gain or a focus on becoming leaner or developing a stronger core. One thing that I always ask my athletes and believe is important is, “You are doing X form of movement. How much effort (%) do you feel you are putting into it? What (%) do you feel your body is giving you in return?” We commonly hear, “I feel like I am giving 130% but getting 80% in return” or “I feel like I am running in quicksand and no matter how much more I am training I am not getting any faster or better”. To compensate for that reduced performance, perfectionism starts kicking in. And it’s like, okay. “Well, I’m not performing like I should so now I’m going to engage in other behaviors like restrictive intake patterns, or I’m going to cut out different food groups, or I’m going to add in additional training or, maybe withdrawing from social settings because I need to focus on training and I do not feel I can be disciplined around friends which makes me more anxious, and I need to focus on losing weight and getting faster or stronger right now.”

These athletes might show signs of avoiding eating in public or abstaining from team meals. They may experience brain fog or they might not appear as cognitively sharp while performing and practicing. Drastic weight changes or training regimens are clear and realistic indications that an athlete might be struggling. Complaints of gastrointestinal distress such as increased stomach pain, nausea, diarrhea, or bloating is also a sign that should increase concern for possible disordered eating. Increased frequency of illness or injuries can be another significant indicator of potential eating disorders or disordered eating in athletes.

Will you please describe how diagnosing an athlete is different than a non-athlete? And why it’s hard to differentiate between healthy exercise and compulsive exercise in an athlete?

This is so difficult because what makes an athlete so great is their dedication, their training, and their athletic ability, and that overlaps a lot with the eating disorder. In sport, a lot of times these things are normalized. It takes time to differentiate, is this a lack of education and knowledge? Is this a true core belief? Is this the eating disorder? It’s critically important to identify the motivation behind the choices that an athlete is making, whether it’s related to food or movement. It’s important to learn what their training schedule looks like. If they’re practicing two hours a day, five days a week, are they also going home and doing additional exercise on top of that or are they doing other clinics or lessons? Are they allowing themselves a day off? So really trying to see what their training schedule is and what’s expected of them versus what additional stressors or training are they adding to their sport. Is this necessary, is this compulsive, or being used as compensation? Again, kind of exploring that relationship with food and their body.

Unfortunately, athletes most of the time are not honest when it comes to screening and questionnaires because they fear getting pulled from their sport or going to treatment. Most of the time, they’re going to deny the severity or they’re going to minimize what they’re feeling and say what they think they need to say to make you happy so that they don’t get pulled. And so it’s really important to make sure you’re screening for that and exploring if they have an unhealthy relationship with movement. If you see them exercising when they’re sick or injured, if they’re starting to feel like exercise is a chore, and they’re not getting joy out of it, but it’s something they have to do, or if a certain workout determines how they feel about their body or food on that day, that would show that there’s a disordered relationship with movement. Red flags for compulsive exercise would be if they don’t allow themselves to have a rest day, they are compulsively tracking intake or workouts, they’re exercising in secret, they are separating themselves from others to exercise, or they’re isolating in order to exercise, or they’re compulsively tracking, those would all be things that really are signs that maybe movement is a little bit less healthy and needs to be explored further.

The big question is always: can these athletes recover from their eating disorder while they continue to play their sport? If yes, what does weight restoration and nutrition therapy look like for them?

Every athlete and scenario is different, and this is where it gets tricky. I personally believe that movement is a critical piece to recovery, & health and well-being. I really want to be able to keep an athlete in their sport. In order to heal that relationship, I think that we also need to evaluate: is this sport and level of participation in the sport healthy for them, or do we need to maybe tone it back a little bit? Is there a possibility to have space to recover and incorporate treatment? If they’re training three to four hours a day, they may not have space for recovery and appointments. We need to see what that looks like for them and what that relationship with movement is like. A lot of times that will involve dialing back the movement a little bit so that we can work on energy balance, like we talked about with low energy availability. We need to make sure that their energy levels are up to adequate levels in order to meet their physical demands. Once those are even, we’ll reassess, and then we can move forward with movement and food, or maybe we need to stabilize there for a little bit. Another piece is that if we do dial back or they need to discontinue sport for just a little bit, we will use that time for functional movement. So practicing embodiment activities whether it’s through stretching, breathing, meditation, yoga, walking, or gentle runs so that they learn how to connect with their body so that if and when they return to sport, they can be even more connected and listen to their body.

Nutritionally, we want to prioritize that energy balance. If they need weight restoration, it’s hard to continue participating in the level of activity most of our athletes are competing in while weight restoring. So the majority of the time, we will need to cut back and/or pause movement briefly in order to get those nutrients restored, and then we can reevaluate. We want to make sure that the plans are individualized for them because the reality is they are an athlete. They’re not a student. They’re not a non-athlete or a normal everyday human. Their nutrition needs are so much more significant than that of a non-athlete, and that can be challenging for our athletes, especially our high school athletes who are trying to figure out how to eat in the lunch room and their nutrition needs are three times those of their peers. Guiding them to recognize the importance of consistent eating throughout the day, even if it doesn’t mirror their peers, and assisting them in structuring their meals around practices, training, or competitions ensures they remain adequately fueled during these activities.

Follow up: If they must leave the sport for more intensive treatment, can they ever return to their sport or any competitive sport?

Yes, I think absolutely if the sport is healthy and safe for them. My goal is to have the ability to choose. I want that to be any client’s option, I want you to have options. I don’t want it to be the eating disorder choosing it for you. A lot of times what we see, especially with our young athletes who have individualized one sport and specialized in that and become elite, we’ll see that they are just kind of going through the motions and they’ve lost the joy in that sport. So we want to evaluate: is this sport supporting your recovery needs? Is this team, coach, or studio supporting recovery, or is it working against it? Commonly we see that our dancers love and want to continue dance, but they feel that their current teachers and coaches are fueling the eating disorder. In this case, we work to find a different studio or teacher that’s better aligned with their recovery goals, and they’re able to flourish in that environment. So, looking to see what’s best for the athlete, or maybe we find different forms of movement that are more empowering and more recovery-aligned.

Finally, how can athletes and parents assess coaches or teams for the potential of eating disorders, if at all? Are there any particular qualities that you like to see in a coach or program that is more supportive for the athlete?

I like to first and foremost have an athlete be a person before an athlete. They are a human. I would love to see coaches, trainers, and parents ask, “What are you doing outside of your sport? What brings you joy? What is something that you have enjoyed this week or that you felt like was a victory?” to help them separate themselves from just being an athlete because they are so much more! Avoid conversations about body, weight, or nutrition unless you’re a professionally trained individual who is specialized in the subject. It’s important to have coaches evaluate how much effort athletes are putting in and what are they getting back from that. Additionally, it is critically important to educate yourselves on the signs and symptoms of low energy availability, RED-S, and eating disorders so that if any of the athletes do present any of these concerns, you immediately recognize it and have someone that you can refer to who is a specialist so that they can get assessed further before the problem intensifies.

Check out Mary-Lauren’s website for more information related to eating disorders in athletes & subscribe to her newsletter here to stay up-to-date with Nutrition DiscoveRD’s services.

Mary-Lauren’s Recommended Resources for Eating Disorders in Athletes:

If you’re ready to take the next step in your recovery journey, let’s talk about how eating disorder recovery coaching may be a game changer for you. I offer a free 25-minute consultation call, let’s get it scheduled here!

Merrit Elizabeth is an Eating Disorder Recovery Coach certified by The Carolyn Costin Institute. She holds a master’s degree in Health Promotion Management and has years of experience working with women with eating disorders.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

next post

previous post

browse categories

read or leave a comment +